According to the recent Ormax Media report the Indian gross Box office stood at Rs 10,637 Cr in 2022, just Rs 300 Cr less than 2019, which happened to be the best-grossing year at the India box office. But there was a major shift that was witnessed in the box office numbers of 2022 compared to that of 2019. In 2022, the share of the Hindi box office saw a downward slide from 44% to 33%, while the Telugu box office gained a share, moving up from 13% to 20%. The films from four Southern languages contributed 50% to the country’s box office (Tamil garnered 16%, Kannada share stood at 8% and Malayalam clocked 6%). Moreover, 32% of Hindi box office came from dubbed versions of Southern films like K.G.F: Chapter 2, RRR, Kantara, etc. The upsurge of the South has taken many by surprise, especially the industry pundits and stalwarts. How did we arrive at this scenario? Is this the new normal, a disruption? Or is it a one-off phenomenon that will slowly subside with time?

Rome was not built in a day — SET MAX set the tone

The sudden meteoric rise of South Indian language films is not really “sudden” and abrupt. The stage for the audience’s euphoria with Telugu, Tamil, Kannada, and Malayalam films over Hindi was being slowly being set for years. In the early 2000s onwards we saw a flurry of South Indian movies (dubbed in Hindi) being telecast on satellite TV channels. SET MAX (or Sony Max) was a frontrunner in this matter. Who did these dubbed Hindi movies cater mostly to? It was not much of the urban elite populace but people from the Tier II, and Tier III cities, rural belt, and more specifically the people who belonged to the lower strata of the society in terms of their socio-economic position. As Bollywood gradually tended towards catering to the multiplex thronging cosmopolitan aspirational crowd, people at the lower end of the spectrum continued to get acquainted, slowly and steadily, with the films and stars of the Southern stars as they watched “Arya Ki Prem Pratigya” (“Arya” in Telugu starring Allu Arjun), “Meri Taqat Meri Faisla” (“Venghai” in Tamil starring Dhanush), Magadheera (“Magadheera” in Telugu starring Ram Charan), “The Fighter Man Singham” (“Singam” in Tamil starring Suriya), “Ek Aur Vinashak” (“Neninthe” in Telugu starring Ravi Teja), “Ek Aur Qayamat” (“Kantri” starring Junior NTR) and many more. The Southern language movies provided them with the needed escapist experience which Hindi films failed to cater to.

A story of empowerment, representation, and cultural pride

According to Deloitte’s 2022 Global TMT report, total smartphone users in India stood at 750 million out of 1.2 billion mobile subscribers in 2021. In the last 5–7 years there has been a huge spurt in smartphone usage in the country. In the rural belt alone smartphone ownership has doubled over the last few years, from 36.5 percent in 2018 to 67.6 percent in 2021. Added to this, the advent of social media platforms like TikTok, Instagram, YouTube, etc just opened up the gates to a tsunami of content creation all across the globe. The medium has helped to empower ordinary citizens by giving them a voice, a platform to reach millions of people. People shared moments from their lives, their performances, their travel stories, and their opinions with the mass audience. The “Kancha Badam” song catapulted the singer Bhuvan Badyakar into an overnight sensation, local cuisines made by people sitting in remote villages became popular through YouTube channels like “villfood”/ “Village Cooking Channel”, individual content creators like Bhuvan Bam, Kusha Kapilla, Aiyo Shradhha, and others made their cut into the entertainment and film industry. The democratization provided millions of people with that sense of being and a sense of representation. As the pandemic set in, it somehow forced people towards being more inward-looking, being aware of self, of our immediate surroundings, our neighbourhood, our city, our roots, and our own culture as a whole. People started valuing their culture which gave them a newfound strength.

Hypermasculinity is the flavour of the season

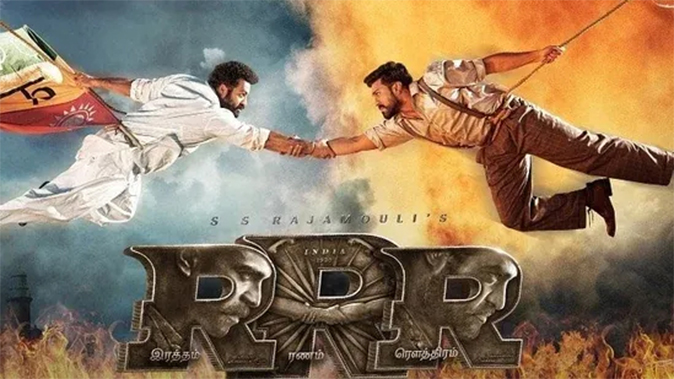

The commonality between the recent blockbusters from South India lies in the fact that the protagonist in each one of the stories is overtly and unapologetically hyper-masculine by nature. Be it Rocky bhai from KGF, Shiva from Kantara, Pushparaj from Pushpa or Bheem & Raju in RRR. In the reel, the characters glorify stereotypical masculinity and tend to applaud violence, which is perceived by the people (especially the youth) to be stylish and manly. In real, the overall political climate that presently exists in the country depicts a similar pattern where authoritative machismo flexes its muscles and thumps its chest bulldozing any opposing force coming its way. Brute force seems to be the flavour of the season and the reel is just reflective of the times we are living in, similar to the rise of Amitabh Bachchan’s “angry young man” image in the 70s which was just representative of the pulse of the general public, who lived their lives with their dreams shattered and no hope to steer them through. In the last ten years or so, people have been fed narratives and slowly ingrained into the societal system which started to “idolise” a colossal figure who is their sole saviour from all their difficulties and problems. Rocky Bhai, Shiva, Pushparaj, Bheem & Raju are mere incarnations of that “him”.

A cycle of success and failure

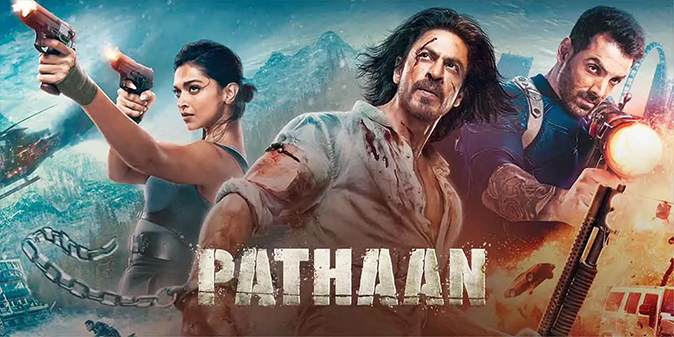

Director S S Rajamouli said in a recent interview, “There’s no good and bad; it’s bigger successes and lesser successes. Even Hindi films have had success in the last six months; it’s not like every Hindi film has been unsuccessful. Also, it’s not like every film from the South has done well. But what [has] happened is that the success of south Indian movies has been much bigger than the success of the Hindi film industry during this season.” He is right. It’s too early to conclude because the fallacy of these trend settings lies in the fact that they are prone to volatility depending on what content is getting released, when it is getting released, and how strategically it is being marketed. It is noteworthy here that in the first two months of 2023, the Hindi Box Office garnered a solid 40% (Pathaan was way ahead of the pack) of the total countries’ BO numbers. These are cycles of successes and failures and will continue to ebb and flow interchangeably with time. At the end of the credits, you shall find just one winner, CINEMA.

Interesting blog post. To answer your question, whether it’s a fundamental shift or passing cycle totally depends on how southern film industry is going to take this shift forward. One of the reasons behind this shift is that audiences of the country are exposed to South Indian content via OTT, YouTube and other digital platforms like never before. 20 years ago, for a south Indian movie to succeed across the country, it must be heavily marketed or should have A-listers like Kamal Hassan, Mani Rathnam. The templatized film making style of the Hindi movie industry also pushed the North Indian viewers to look for content across the country. Slowly, viewers started appreciating South films. Now, they are going beyond not just seeing the actors on screen, but also showing interest in knowing the people behind the screen. The rising popularity of Rajamouli, Lokesh Kanakaraj, Vetrimaaran are examples of this trend. We also see a lot of efforts being put in to make “Pan Indian” (flavor of this season) movies. South Indian filmmakers have tactfully dealt this trend by casting North Indian stars (Ajay Devgn in RRR, Sanjay Dutt and Raveena Tandon in KGF2 and many more examples) in their movies which gives the movie a Pan Indian appeal.

As a South Indian, I am personally glad that North Indian audiences are now being educated about the different film industries in the South. Whether or not the dominance will continue, we must wait and watch.